Radiography of the Sella Turcica

The sella turcica (also called the hypophyseal fossa or pituitary fossa) is a midline saddle-shaped depression in the sphenoid bone that is lined by the dura mater. Although it is a relatively small area, it is an extremely valuable piece of real estate in the brain because it forms the bony seat for the pituitary gland which it houses and partially encloses. One of the main reasons for imaging the sella turcica is that it is a window to the pituitary, a pea-sized gland that is often called the master endocrine gland because of the major role it plays in regulating vital body functions. Sellar components are easily demonstrated by several radiographic planes and angles. Radiology techs need to be aware of the anatomy of this region as well as correct radiographic angles and patient positioning techniques to demonstrate the sella turcica and surrounding structures accurately.

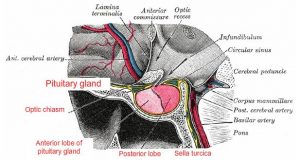

Many disease processes originating inside and outside the cranium cause radiographic changes in the pituitary fossa or sella turcica. These radiographic changes are valuable diagnostic aids for a number of endocrine disorders. For example, enlargement of the sella turcica or distortions in its shape and contour may be related to pituitary pathology. The sella turcica is located deep within the cranium but can be demonstrated on a number of projections used in skull radiography. This picture of the skull (with temporal and parietal bones removed) shows the location of the sella in red.

Anatomy of the Sella Turcica

The anterior, posterior, and inferior walls of the sella turcica are bony while the lateral walls and roof are made of dura that slings between the anterior and posterior clinoid processes. The dural roof of the pituitary fossa has fenestrations for the infundibulum. The terms sella turcica and pituitary fossa are often used synonymously, but in fact the pituitary fossa has 4 parts:

- Tuberculum sellae (anterior)

- Dorsum sellae (posterior)

- Diaphragma sellae (superior)

- Sella turcica (inferior)

In addition to the pituitary gland, the pituitary fossa contains the pituitary vessels, the anterior and posterior intercavernous sinuses, and cerebrospinal fluid. Surrounding anatomical structures include the sphenoid sinus, clivus, brainstem, basilar artery, infundibulum, optic chiasm, hypothalamus, and cavernous sinus. In normal individuals, the sella turcica is less than 15 mm long and less than 12 mm deep.

Radiographic Signs Associated with Pathology of the Pituitary Gland

Changes in and around the sella turcica can reflect numerous intracranial pathologies, not limited to the pituitary gland. Here are some of the common radiographic findings in the sella turcica and associated pathologic conditions:

- Enlargement of the sella turcica associated with empty sella syndrome

- Small sella turcica associated with pituitary insufficiency

- Distortion in shape and contour associated with pituitary tumors

- Bony density of the margins with thinning seen in empty sella syndrome

- Erosions in the floor or lateral walls due to aneurysms or chronic increased intracranial pressure

- Thickening of the tuberculum or clinoid processes due to meningioma of the sella turcica

- Sclerosis of the sellar floor associated with nasopharyngeal carcinoma or craniopharyngioma

- Fat or calcifications in the intrasellar, suprasellar or parasellar region may be indicative of germ cell tumors or craniopharyngioma

- Eggshell calcification patterns may be demonstrated in the presence of aneurysms

Pathological Conditions of the Sella Turcica

Empty Sella Syndrome

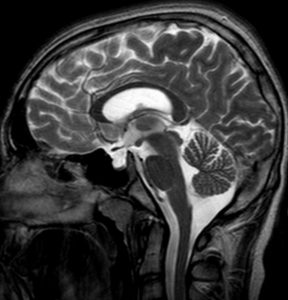

This is a rare disorder in which an enlarged or malformed sella turcica is partially filled with CSF and contains a tiny pituitary gland (partially empty sella) or the pituitary is not visualized (completely empty sella). The condition can occur as a primary disorder (idiopathic) or secondary to head trauma, following treatment for pituitary tumors, or in association with benign intracranial hypertension (pseudotumor cerebri). Many people with empty sella syndrome are asymptomatic, although there are concerns about hormone deficiencies. The hallmark radiographic finding is, as the name suggests, an empty sella turcica. The pituitary tissue is largely replaced by CSF. On lateral skull X-ray, the appearance cannot be differentiated from pituitary masses, such as macroadenoma. An enlarged fossa is seen with thinning of the margins. The picture below shows a T2-weighted MRI in a patient with empty sella syndrome.

Pituitary Adenomas

These are primary tumors of the pituitary gland and are a common type of intracranial neoplasm. They are almost always benign with no malignant potential. They are classified as pituitary microadenomas (less than 10 mm in size) and macroadenomas (more than 10 mm in size) and present different imaging and surgical challenges. Patients with pituitary adenomas present either due to symptoms related to hormonal imbalance or due to mass effect on adjacent structures, most commonly the optic chiasm. The primary imaging modality for pituitary microadenomas is MRI with a sensitivity of up to 90 percent. Pituitary macroadenomas are seen on plain radiographs as masses arising from the gland and typically extending superiorly. Cavernous sinus invasion is often seen with prolactin-secreting tumors. Bilateral indentation of the superior part of the fossa (diaphragma sellae) gives a characteristic figure-of-eight, snowman, or dumbbell configuration, which is a feature that aids differentiation from meningiomas of the pituitary fossa.

Non-Pituitary Tumors of the Sellar Region

Non-pituitary sellar tumors such as schwannomas, hemangioblastomas, primary sellar melanomas, and cavernous angiomas may clinically mimic pituitary adenomas or other sellar tumors.

Craniopharyngiomas

These relatively benign tumors arise typically in the sellar/suprasellar region. Patients typically present with symptoms such as headache, visual problems, hormonal imbalances, and behavioral change due to frontal extension. Imaging features depend on the tumor type. Adamantinomatous tumors are large with a lobulated contour, solid and cystic components, and stippled peripheral calcifications. Papillary craniopharyngiomas are spherical and solid, lacking a prominent cystic component, and calcifications are rare.

Pituitary Apoplexy

This is an acute syndrome with clinical signs and symptoms including headache, alteration in mental status, visual deficits, and oculomotor palsies. In a large percentage of cases there is an associated pituitary macroadenoma present, but rarely, apoplexy can occur in a healthy gland. Radiographic features include an enlarged gland with macroscopic hemorrhage and surrounding edema.

Intrasellar Aneurysms

Aneurysms that project into the pituitary fossa are associated with radiological features such as erosion of the lateral wall of the sphenoid sinus and filling defects in the cavernous sinus. Distinguishing features that indicate pituitary tumor (rather than aneurysm) include complete erosion of the fossa, bilateral displacement of the cavernous sinuses, and soft tissue opacity in the sphenoid sinus.

Rathke Cleft Cyst

This is a remnant of a fetal connection between the nasopharynx and hypothalamus which obliterates during normal development. This benign cyst is usually intrasellar when small but may extend to the suprasellar area when it grows.

Radiography of the Sella Turcica

In the past several decades, investigation of the pituitary and sellar region with radiographic imaging has undergone significant advancement. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have largely replaced plain radiography, cerebral pneumography, and angiography due to a superior ability to delineate soft tissues. MRI is the modality of choice for the evaluation of sellar and parasellar lesions. Nonetheless, X-ray remains a useful tool that can yield valuable diagnostic information about pathology in this region. Plain radiography may be used for screening purposes or to identify calcifications and/or destructive changes of the sella turcica and adjacent bony structures. The sella turcica is best demonstrated on lateral radiographs of the skull. The floor can be visualized on angled frontal radiographs, such as the Caldwell view.

Radiographic Projections of the Sella Turcica

Skull Lateral Supine: A right or left non-angled lateral view of the skull demonstrates details of the cranium on the side closest to the IR. The sella turcica and dorsum sellae are visualized in profile on this projection. In a properly positioned lateral skull X-ray, the line extending from the outer canthus of the eye to the external auditory meatus is perpendicular to the table and the anterior and posterior skull is visualized.

Skull PA Axial (Caldwell View): This is a caudally angled occipito-frontal projection that demonstrates the floor of sella turcica. In a properly positioned Caldwell projection, the IR is perpendicular to the orbitomeatal line (OML) and the X-rays pass at an angle of 15 degrees from behind the head and exit at the nasion.

Video Credit : Jeremy Enfinger

Skull PA Axial (Haas View): This is an occipito-frontal projection that is angled 25 degrees cephalad to the orbitomeatal line (OML). The patient sits or stands facing an upright Bucky with the forehead and nose touching the IR. The neck is flexed to bring the OML perpendicular to the IR. This projection can also be done with the patient prone. The midsagittal plane is aligned perpendicular to the Bucky and the rays are angled at 25 degrees cephalad to the OML. The patient’s head should not be rotated or tilted. This view demonstrates the dorsum sellae in the shadow of the foramen magnum.

Video Credit : Chase Smith